The 59 Club by Stuart Barker

In the 1960s, the 59 Club was the biggest, most famous motorcycle club in the world, and a notorious hangout for outcasts and misfits. Half a century later, the incredible story of a gang of hoodlums and a pair of leather-clad vicars continues to amaze.

If you rode a motorcycle and wore a black leather jacket in London in the 1960s, there were few places you’d be welcome. The Biker Boys of the time had such a bad reputation that most cafés, cinemas and clubs banned them. The only place they could congregate was at a truck stop in North London called the Ace Café. There, the original ton-up boys would work on their bikes, swap tales of riding exploits, eat greasy trucker food and take part in illegal burn-ups. A favourite pastime was to put a rock’n’ roll record on the jukebox and race each other round the block, trying to get back before the song had finished.

If you didn’t ride a bike and didn’t adhere to the ritual dress code of leather jacket, duck’s arse haircut and battered jeans, you didn’t dare go to The Ace. Many citizens were terrified to even pass the place. In polite society, these disaffected young men had no friends. They were outcasts, despised and feared in equal measure.

Like everyone else, the late Father Shergold (1919-2009) feared the Rockers who hung out at The Ace but, being a keen bike rider himself, he felt they could be ‘saved’ from a life of crime if they had some purpose and somewhere to belong. In the November 1966 issue of Link – the magazine of The 59 Club – Father Shergold recalled: “Because of their dress, their noisy bikes and their tendency to move in gangs, nobody wanted them. Dance halls refused them, bowling alleys told them to go home. Youth clubs were afraid of them. Even transport cafés didn’t welcome their custom.

Shergold wanted to go to the Ace and give out religious posters for the benefit of the bikers but feared the reception he would get. Eventually he decided to try. Concealing his dog collar under a white scarf, he rode off on his Triumph Speed Twin. Father Shergold’s recollection of the trip shows the terror which the Biker Boys instilled.

“Just past Staples Corner about a dozen bikes, ridden by sinister figures in black leathers, roared past in the opposite direction. I felt sick with fear. By the time I reached the bridges at Stonebridge Park I was in such a panic I opened the throttle and fled past the Ace as fast as I could. I realised I was being a coward, so I turned back. Again panic seized me and I went past. Then I turned back again and finally rode into the forecourt. By now, the Ace was practically deserted but I consoled myself that I had at least penetrated into the lions’ den, even if the lions were out on the prowl.”

Father Shergold returned a few weeks later, armed with leaflets and making no attempt to hide his dog collar. “It was packed. Hundreds of boys were milling around, laughing and talking. I thought, ‘This is it. I shall almost certainly lose my trousers or land up in the canal’.”

But there was no need to worry about getting a ritual dunking. Father Shergold was treated with every courtesy and was amazed at the positive reaction he got when he invited the bikers to attend a special service specifically for bikers at his church the following evening. Father Shergold arranged to have various bikes on display in the church itself and, incredibly, some bikers even wheeled their machines into the church to be blessed!

The service was packed, and the incongruous sight of dangerous, law-breaking bikers attending church proved irresistible to the media. “In my address I compared the motorcyclist to the knights of old,” said Shergold later, “and suggested we should try to uphold the same ideals of courage, courtesy and chivalry.”

The following day, Father Shergold’s service was all over the television news, and headlines in the national press proclaimed ‘Ton-Up Bikes Blessed’, ‘Ton-Up Kids in Church’ and ‘Pictures of 100mph Gang that may cause a Storm.’

Impressed by the turnout, Father Shergold realised the Bike Boys needed a place where they could hang out and socialise. Father Shergold had already been involved with a church-run youth club called The 59 Club, which had been founded by the Reverend John Oates. It was opened in 1959 by Cliff Richard and Princess Margaret, and Cliff and The Shadows (who had just hit it big with the single Move It) played at the opening night.

The club was based at the Eton Mission in Hackney Wick and Father Shergold thought it would be an ideal place for his Bike Boys to hang out. In October 1962, the first bikers night was held and attended by around 100 riders. Things just grew from there. The Bike Boys kept the name of the youth club even though theirs was a separate venture. Within a few years they would make the name famous the world over. The 59 Club grew into the biggest bike club in the world with more than 11,000 members, and the club’s roundel badge with the number ’59’ in the centre became the envy of bikers everywhere.

It was in the same year of that first meeting – 1962 – that Father Shergold brought in another priest, Father Graham Hullett, to help him run the club. Soon there were so many members that new premises had to be found and the club moved its HQ to Paddington in central London. Father Graham also rode a bike and he too saw something in the bikers that the rest of society failed – or refused – to see. “These were the same kind of lads who would have been flying Spitfires or bombers in defence of their country 20 years earlier,” he says now. “Other members of the church thought myself and Father Shergold were very brave, but we weren’t really – we were just mixing with people who rode bikes. Being a biker myself, I saw these lads as being just as good as anyone else. They had a different way of life but they were just as good as the rest of mankind.”

Father Hullett soon became heavily involved in the club, and gained a reputation as a man who would do anything to help those in trouble. He used his own money to bail wayward members out of jail, he broke up fights and smoothed nasty situations over, and even loaned his own money so that 59ers who were broke could take part in the annual pilgrimage to the Isle of Man TT races. One member who remembers his kindness is Len Paterson who, as a 17-year-old, was a self-confessed delinquent who was heading for a long stretch in prison before the 59 Club saved him.

Even before he gained his bike licence, Paterson had black marks against him. “I started riding at 14 and had my first endorsements before I got my licence,” he remembers. Paterson was unemployed when Father Hullett discovered he was so broke he couldn’t join his fellow club members at the TT. Hullett loaned him the equivalent of two weeks wages to go to the races. “I had a fantastic time at the TT,” says Paterson, “and I’ve been eternally grateful to Father Graham for the chance to go. He was a rock and he was one of us. Although he wore a dog collar, he was really approachable and he never once talked about God or religion to me – he seemed happier talking about bikes.”

It took him two years, but Paterson paid back every penny. He also remembers Father Hullett helping him out of a more desperate situation. When one club fight got out of hand and ended up with Paterson severing another man’s jugular, Father Hullett again came to the rescue. “The guy was lying on the floor with a fountain of blood spouting out of his neck,” recalls Paterson.” I thought I’d killed him. But Father Paterson somehow sorted it all out, the guy survived and it didn’t go to court. I had already been nicked for threatening behaviour and actual bodily harm and had that gone to court my life would have been totally different. I was a yob and would have ended up in prison had it not been for Father Graham.’ There were other times when Father Hullett faced down violence. He once tried to stop a member of The Road Rats biker gang coming into the club with a shotgun, breaking the gun-toting biker’s fingers as he pushed him back. “The Road Rats were a good group,” Hullett says, “but our club had a policy of only letting in real bikers or pillions. The Road Rats were mainly bikers but they had a lot of hangers on. I used to stand at the door and let in the genuine bikers while refusing entry to others. I got nervous because I knew some of them had shotguns. One time a biker I knew well shot and killed another biker on Chelsea Bridge. I was pretty nervous most nights.”

Where did all the Rockers go?

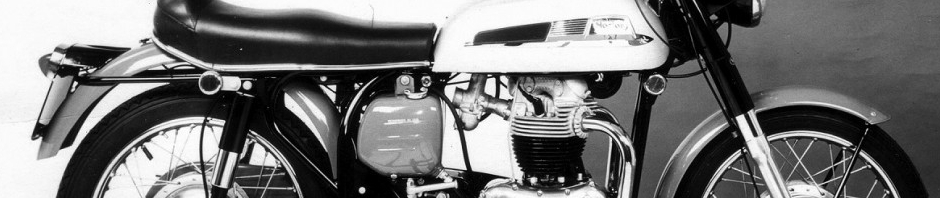

The ‘Bike Boys’ or ‘Rockers’ of the 60s rode the most powerful sports bikes of their time, wore leather jackets, went to race meetings and hung around in cafés. Sound familiar? Rockers didn’t really fade away, they simply evolved.

Today’s sports bikes may be R1s, Blades and GSX-Rs, not Nortons or Triumphs, but most owners still add race exhausts or rearsets, just as the original ton-up boys added clip-ons and racing screens. The leather jacket has evolved into the one- or two-piece suit and, while the annual pilgrimage to the Isle of Man TT is still a must for many, today’s Bike Boys are just as likely to head to Brands for WSB or Donington Park to watch MotoGP. The Ace Café, original haunt of the Rockers, is still in existence, but most riders still know a café where they meet for a Sunday run. Then, as now, a large section of the public think bikers are noisy, no-good hooligans – no change there, then…

In essence, little has changed. While there’s no longer such a link between rock’n’roll and biking, you’re still more likely to find hard rock bands playing at bike meets, not Westlife. Most riders of modern sports bikes can trace their ancestry back to the Bike Boys of the 1960s. The desire for freedom is still there, the thrill of chasing the magic ton has perhaps been replaced by the buzz of a track day, but the rebel image has not completely disappeared. Strangely, no-one referred to those pioneering bad boys as ‘Bikers’ – it was always ‘Bike Boys’, ‘Rockers’, ‘Leather Boys’ or ‘Ton-up Boys’.

Today, we are known as ‘bikers’ but then what’s in a name? The spirit of those 60s rebels who found the true meaning of life in a powerful motorcycle lives on in all of us.

And that’s something to be proud of.

gihv8e

2rj5rg

epsw7z